Robinhood: The Tension Between Good And Evil

Addiction, Betrayal, and the Rise of the Retail Investor

Welcome to the 107 new and curious minds who have joined The Operator since July 1! If you are reading this but have not subscribed, join the 107 others by subscribing here!

If you don’t have time to read and would like to download this episode straight to your ears, you can find this essay in podcast fashion here.

I have this deep-seated, almost visceral sense about the present article. Suffice to say, when it comes to my feelings on Robinhood, it’s complicated. That said, it seems fitting my first Substack post is on this topic.

Let me set the stage.

In the investment community, declaring you use Robinhood seems almost politically incorrect; something that shouldn’t be advertised. It’s polemical, and solicits a deep, almost subterranean sense of betrayal. The events of 2020 and early 2021 fissured what was once a gleaming, democratic, power-to-the-people brand. Retail investors viewed Robinhood as a place to participate in The Great Investment Game, that Robinhood was not like the innumerable indifferent institutional trading platforms. But it turns out Robinhood is like the others. It’s a for-profit FinTech colossus in a kill-or-be-killed industry, valuing itself at $55 Billion on the secondary market.

There’s something about feeling betrayed by an entity you trusted that cuts to the quick. Feathering salt into this wound is apocryphal PR management, an almost impetuous refrain of ‘retail investor empowerment,’ and undeterred supersonic user growth.

I want to take a position here. I want to be swept into the anti-Robinhood retail investor tidal wave and arouse hostilities. Joining the revolution and being a part of something bigger than myself are such fundamentally human pursuits – I am tempted. But that’s not what this article is about. I aim to paint this company for you, noble reader, in all its colors, with even brushstrokes.

My research and use of Robinhood’s offerings is extensive, and I extend this information freely, so that you might choose a side to take a seat of your own.

It was a snowy November day in Denver, 2016…

My investment journey began at the end of my third year of medical school. I had completed my core curriculum and was surprised to find myself with a bit of free time, a first in almost a decade.

I had just downloaded the Robinhood app, and I remember gravitating immediately towards its slick user interface, frictionless sign-up-and-go design, and the absolutely intoxicating experience of purchasing my first stock. I had anxiously followed a small universe of tickers for a week or so, and finally pulled the trigger, buying Bank of America at $22.50/share.

It was electric. The market order went through and confetti shot across the screen, celebrating the purchase and locking in an overpowering and dopamine-driven mini-euphoria. I was hooked. I had never before felt so close to being a business owner, to financial independence. Mind you, I wasn’t buying SpaceX or Stripe – I was buying Bank of America – one share. It didn’t matter. I fell in love with equity investing in that moment, and have used Robinhood to make trades ever since.

Can you begin to see why villainizing this platform might give me pause?

We will unpack all of it. All the mess, the missteps, the concerns and the green shoots. The good and the evil. In today’s article, I dive deeply into Robinhood’s many facets, with particular treatment of the following:

· Robinhood’s founding mythology & early days

· Moats won and moats lost

· “A Rat and a Liar”

· Key takeaways from the Robinhood S-1 and the coming IPO

· What price would I buy $HOOD at?

· Closing Thoughts

Robinhood Origin Story: A Meeting Of The Minds

Bulgarian-born Vladimir Tenev met his Robinhood co-founder and former co-CEO Baiju Bhatt while studying physics at Stanford. Their similarities bordered on eerie: both only children of immigrant parents (Bhatt’s parents emigrated from India) who grew up in Virginia, both long-haired physics majors who spent their youths contemplating esoteric maths.

Source: Bhatt & Tenev, Robinhood.com

Following graduation, both went their separate ways to attend prestigious math universities, reconnecting in 2010 to start Celeris, an algorithmic trading startup. Celeris was a short-lived venture quickly abandoned and they soon launched a financial software company called Chronos Research, which focused on low latency algorithmic trading.

While neither Celeris nor Chronos were particularly successful, these startup experiences set the stage for their third, most successful venture. In How I Built This, Tenev describes three conditions that formed the impetus for Robinhood’s founding:

1.) The Occupy Wall Street movement: Living in New York, Tenev remembers walking through ‘tent cities,’ occupied by those bankrupted in the 2008 financial crisis. There was a growing sense of mistrust with financial institutions; that the game was rigged. The cultural climate was ready for a change of season.

2.) Realizing trading does not require commissions: While working at Chronos, Tenev and Bhatt witnessed hedge funds make millions of trades daily, paying fractions of a penny per trade. Despite this, individual Americans were charged $5 – $10 commissions by major brokers. Tenev and Bhatt derived making a trade costs essentially nothing, and that trading could be offered gratis.

3.) The rise of mobile technology: In the early 2010’s the industry was awash with fresh mobile applications that challenged conceptions of mobile phone capabilities. In 2010 alone, powerful social applications like Zynga, Groupon, Tumblr and Foursquare were launched. These applications were built for the young, mobile consumer, who increasingly expected a similar experience. As none of the major trading brokers were providing this, an opportunity crystalized for a duo of perceptive entrepreneurs.

From these three insights, an idea began to take shape. A massive, ambitious idea that coupled disruptive technology with the revolutionary soul of Bastille Day: a mobile application with free trading for everyone.

And so, Tenev and Bhatt got to work developing a beta of the app, moving to San Francisco in the process. One year into development, Tenev and Bhatt still hadn’t settled on a company name. The front-runner for the majority of the launch preparation was actually the very unfortunate, “CashCat.” Fortunately, Tenev’s then girlfriend (now wife) helped nudge them in the right direction.

“The working title was actually CashCat…but there was a feeling it wasn’t powerful enough. And so the way my wife would introduce me to her friends and other people is, you know, “This is my boyfriend Vlad, he’s in finance.” And then there would be this groan, right, because they thought I was like this investment banker. But then she would be like, “Oh no no no, they’re the Robinhood of finance. They’re building something for the little guy.” And so, the name Robinhood kind of stuck.”

Vlad Tenev, Robinhood co-founder and CEO, emphasis mine

New name attached and with official launch in their sights, the Robinhood founders began to employ two marketing tactics that would go on to become the major themes of retail investing: FOMO and Gamification.

Tenev and Bhatt posted a landing page where an individual could simply submit their email address and be added to the Robinhood waitlist. Effectively, they built a digital velvet rope in front of their app, and then gamified the process, allowing users to jump ahead in line if they referred friends.

The result?

By the time Robinhood officially launched in 2015 they had almost 1 million emails on the waiting list. Conversion had never been easier, and CAC never cheaper. Like Facebook or Instagram, Robinhood built a product that was free, intuitive, and addictive. They were off to the races.

In the years since, Robinhood has posted blistering growth rates fueled by $5.6 Billion in funding, triggering a renaissance of retail investing and a cocktail of compelling products laced with FOMO and gamification.

How Robinhood Makes Money: Casino Royale

Free trading was completely novel when Robinhood first launched, with competitors Schwab, TD Ameritrade and E-Trade charging $5 - $10 per trade. While a commission fee is a small hurdle for wealthy or middle class Americans, it effectively excluded a large portion of younger or lower-earning individuals. Robinhood capitalized on this underserved segment to build a powerful wedge into the brokerage business.

But how does a stock broker that doesn’t charge fees make money?

Although Robinhood trades are technically commission-free, they were and are, by no means, “free.” In the S-1, Robinhood outlined three business segments, transaction-based revenues, net interest revenues, and ‘other revenues,’ which I will cover below.

Payment For Order Flow (PFOF)

PFOF (pronounced “pee – foff”) is perhaps Robinhood’s most controversial revenue stream, and you will hear this term flying around as the IPO nears. It doesn’t help that Bernie Madoff, famed Ponzi architect, was the first prominent practitioner of payment for order flow. That said, it is a common business practice for brokerages like those listed above, as well as recent FinTech entrant and Robinhood rival, SoFi (SOFI). While Robinhood was onboarding millions of users to its ostensibly fee-free platform, PFOF ensured the lights remained on and the toilet paper fully stocked.

In its most basic form, PFOF is the compensation a broker like Robinhood receives for routing customer orders to a market maker like Citadel. This could be a routine buy or sell order, or something more complex, like an options or cryptocurrency order. To understand PFOF one layer deeper, you must understand the bid-ask spread.

The bid-ask spread is the difference between the highest price an individual is willing to pay for a stock and the lowest price another individual is willing to sell that stock for. The bigger this spread, the bigger the potential profits for market makers. Robinhood sells digital receipts of its clients’ orders to these market makers, who buy and complete the order.

These market makers ingest millions of such orders, seeking to execute the trade at the widest bid-ask spread, pocketing the difference. The potential profitability of PFOF doesn’t stop there; by having access to millions of trades, market makers with sophisticated analytics benefit by knowing which direction the financial puck is moving well before others.

There are some obvious and perhaps less obvious reasons for the controversy enshrouding this practice. Robinhood’s ‘How Robinhood Makes Money’ page on their website outlines their various revenue streams. PFOF was notably absent on this page for the first three years following Robinhood’s launch, although this segment constituted the vast majority of Robinhood’s revenue. Indeed, if you go to Robinhood’s website today, PFOF remains absent, and is actually referred to as ‘Rebates from Market Makers and Trading Venues,’ an exceedingly opaque (and intentional) substitution.

Source: Robinhood

The SEC found Robinhood training documents for customer service representatives in early 2018 explicitly instructed them to “avoid” discussing payment for order flow, stating it was “incorrect” to identify PFOF in response to the question regarding how Robinhood makes money.

Furthermore, the SEC found Robinhood falsely advertised the quality of its order execution. ‘Price improvement’ is the concept that the order of a retail stock trader is executed at the best possible price in a liquid market. A 2019 internal investigation conducted by Robinhood stated “[n]o matter how we cut the data, our % orders receiving price improvements lags behind that of other retail brokerages by a wide margin.” Between October 2016 and June 2019 Robinhood’s customer orders lost a total of $34.1 million in price improvement compared to what individuals would have received at competing brokerages, even after assuming those brokerages would have charged $5 per order.

And PFOF business is booming. In 2020 Robinhood grew PFOF revenues an eye-watering 321%, and includes everything from routine equity and crypto trades (crypto PFOF is called “Transaction Rebates”) to options trading. But of all the trades Robinhood can score commission on, options trading is the Wagyu ribeye, netting 3 – 4x more profit than an equity trade.

Hmm...more on this later.

Robinhood Gold

Source: Robinhood

Robinhood Gold is a monthly premium subscription service, and impacts both net interest revenues as well as ‘other revenues.’ For $5 per month, users have access to Nasdaq Level II market data and reports, as well as margin investing. This subscription service racked up $27.7 million in Q1 2021, up 254% year over year, and represented 5.3% of total revenues.

However, it is the margin investing, rather than subs, that drive interest revenues for Robinhood Gold. If a Robinhood user elects to use, say, $10k of “Robinhood Gold” funds to make their own trades, Robinhood will charge that user 2.5% annually (charged on a monthly basis). This interest rate was kindly halved from 5% in December, 2020.

Recent market crashes have demonstrated the dangers of margin investing. As an example, if a user who deposited $10k in Robinhood also borrows $10k in Robinhood Gold margin and invests these funds in the market, their Robinhood balance will show $10k (even though $20k is invested). If the value of these investments rise by 30%, the balance will show $16k, an effective 60% gain! Conversely, if the value of these investments depreciates by 30%, the balance will show $4k (the loss of $6k comes only from the investor’s principle). This can trigger ‘margin calls,’ in which Robinhood demands additional funds be deposited to the account or improves account liquidity by exercising sales of a users’ shares at the current price.

As someone who has been the victim of selling into a margin call, believe me when I say it feels like getting mugged. It is financial violation.

Margin lending is growing slower than subscription revenue but from a much larger base. In 2020, Robinhood’s net interest revenues (including margin lending) were $177 million, growing 151.3% year over year, and representing 18.5% of total revenues.

Cash Management

Source: Robinhood

Robinhood Cash Management places client uninvested cash in Robinhood-partnered FDIC-insured banks, allowing Robinhood users to earn interest paid monthly. Furthermore, Robinhood released a debit card (with some pretty cool designs above) that can be used to spend directly from the brokerage account. While Cash Management was initially announced with an APY of 2.05%, based on my checks today, that APY has fallen to 0.30%.

There are several other ways in which Robinhood collects revenues, including stock loans, income from cash, and proxy service revenue. Stock loans is the practice of lending margin securities to counterparties (like market makers, hedge funds and short sellers), and shockingly represents 10% of Q1 2021 total revenue. While there are understandable concerns about this process, I believe they go hand in hand with PFOF, and will not double tap here. Income from cash and proxy service revenue are not material at this time.

As I hope is evident, each of Robinhood’s three business lines is thriving, with triple digit revenue growth rates across the board.

“A Rat And A Liar”

But even the most compelling business models are vulnerable, and flying close to the sun can be perilous.

Multiple times over the past two years insane trading volume has crumpled Robinhood’s platform with outages. If you follow technology companies at all, you know how embarrassingly painful it is for an app or website to go down. That pain is multiplied when the monies of millions is at stake. Glitches can be similarly excruciating.

On June 12, 2020, 20 year old Robinhood user Alexander Kearns committed suicide after seeing a negative $730k balance on his Robinhood app. He left a note for his parents, which contained the poignant question, “How was a 20 year old with no income able to get assigned almost a million dollars worth of leverage?”

The most recoiling aspect of this tragic story? The negative balance was listed as a mistake; Alex didn’t actually owe $730k.

Source: CBS News

In response to the massive outcry following Kearns’ death, Robinhood abandoned confetti animations celebrating trades, increased educational infrastructure and customer support materials. They doubled down on a promise to prevent this from happening ever again.

(Brief aside — if you or someone you know is hurting, regardless of cause, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HELLO to 741741, the Crisis Text Line).

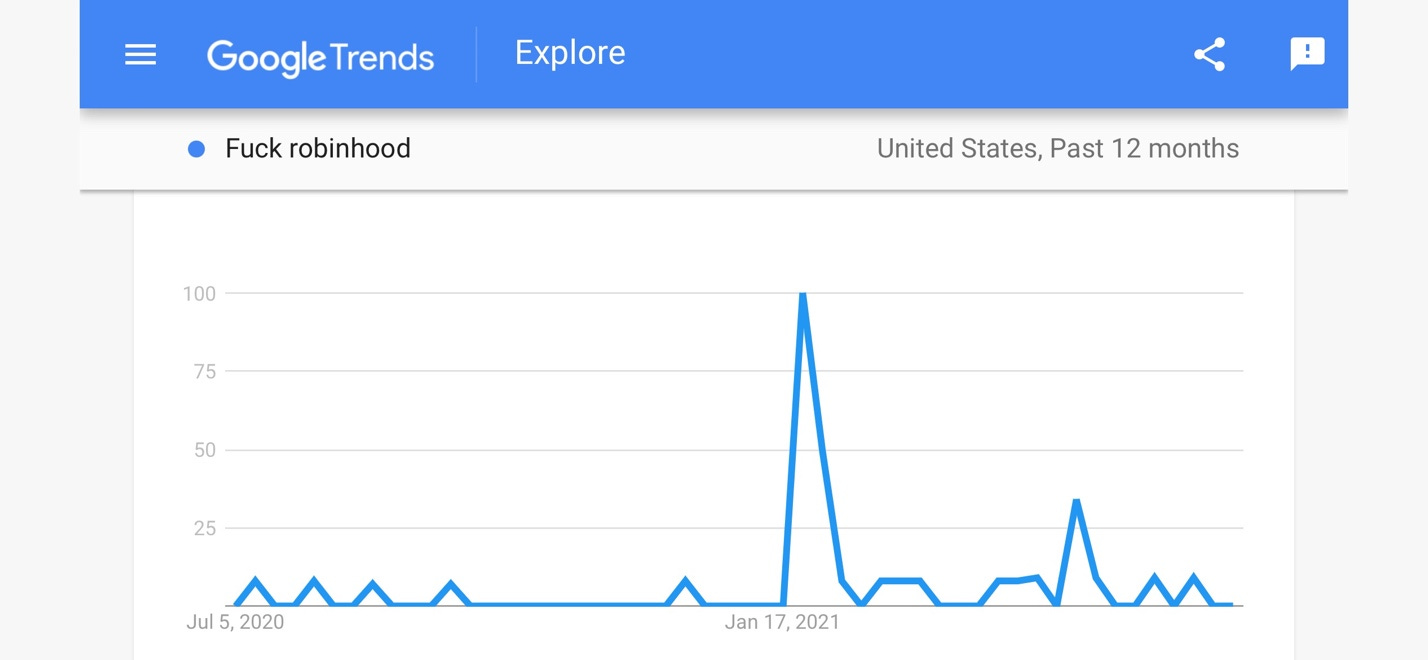

Fast forward to January 28, 2021, and Robinhood is embroiled in a whole new PR nightmare. At the very peak of meme stonk trading, Robinhood halted buying on particularly volatile investments, such as GameStop (GME) and AMC. Millions of retail investors who owned these investments could only hold or sell, which resulted in an obvious stock plummet and a cohort of vengeful bagholders.

Interestingly, just a few days before Robinhood halted buying, Citadel, to whom Robinhood sends more than half its order flow, bailed out hedge fund Melvin Capital to the tune of $2.75 Billion (together with Point72 Asset Management). Melvin Capital was one of the largest short sellers of $GME, for which the bailout was required. Understandably, questions regarding Robinhood’s role in this melodrama and possible conflicts of interest, arose.

Tenev was ultimately brought before Congress and his cell phone was seized by the Feds. To make matters worse, shortly after Robinhood was handed a $70 million dollar fine by FINRA in connection to outages of 2020.

Tenev spent the ensuing months recovering from what was, by all accounts, one of the most unfortunate PR blunders in recent financial history. His initial statements defending Robinhood’s actions were inconsistent, convoluted, and spurred geometrically more narrowed eyebrows than begrudging nods of understanding.

At one point, Barstool Sports President Dave Portnoy interviewed Tenev, calling him “a rat and a liar.”

But the truth behind Tenev’s actions is much simpler than the young CEO made it out to be. Robinhood got a 3 am call from its clearing house that it needed more collateral against the fantastically high volatility of its trading platform. The amount requested? $3 Billion. So Robinhood got to work, limiting buy orders to improve liquidity, and desperately calling investors for capital to avoid a liquidity event. Robinhood raised $3.4 Billion in convertible notes from long term backers Ribbit Capital, New Enterprise Associates and Sequoia Capital. These notes were acquired at a 30% discount (true value closer to $5 Billion), so Robinhood posted a $1.5 Billion loss from this change in value for the quarter ended March 31, 2021. Ouch.

Knowing this history, it’s easy to see why Robinhood has suffered so much backlash, and why many believe so vehemently Robinhood is evil.

Regardless of your opinion on Robinhood’s management of this situation, the company appears to have taken steps to remedy the numerous issues exposed in the GameStop debacle. In the S-1, a full tripling of customer service staff alongside infrastructure investments to endure even 30x the volume of 2020 and 3x highest volume ever seen on the Robinhood platform. Future prophylactic investments in this area are required, especially in light of Robinhood’s audacious growth trajectory.

Robinhood: Moats Won and Moats Lost

Now that we have established Robinhood’s history and a 30,000 foot view of its business model, allow me to roll in the microscope for some granularity.

Earlier this year I read a gorgeous piece by Packy McCormick of the much-loved Not Boring Substack, entitled Stripe: The Internet’s Most Undervalued Company. In it, Packy references Hamilton Helmer’s seminal 7 Powers, a fascinating briefing on the seven moats a business can leverage to make itself “enduringly valuable.” These moats are scale economies, network effects, switching costs, process power, counter-positioning, cornered resources and branding.

Understanding these moats and how a business might deploy and defend them offers retail investors like myself a prescient perspective. Stock prices and relative valuations careen wildly on a given day, equally susceptible to fundamentals, JPOW tweets and the errant beat of a butterfly’s wings.

But moats, by definition, represent enduring value for the company that builds them, which transcends short term vacillations. Therefore, if I can learn to recognize moats in the companies I invest in and write about, I may better frame the future outcome of that business. I applied this learning to Palantir (PLTR), a heinously misunderstood company with vast but often superficial coverage, publishing Palantir: On Building A Dynasty, on Seeking Alpha. As McCormick made the case that Stripe has seven moats, I did the same for Palantir.

Unfortunately, Robinhood is neither Stripe nor Palantir, and cannot claim each of the seven moats. Based on my analysis, Robinhood benefits from two moats, is building three, and lost one. The last seems largely ignored.

Robinhood’s Scale Economies

The quality of declining unit costs as volume increases

While Robinhood is a digitally native technology company, and all such companies benefit from scale, I could not identify any competitive advantage for Robinhood here over peers.

You should expect us to continue to pass back value to our customers, charging lower fees over time as we achieve greater scale and operational efficiency. We will continue to launch new products that strive to be 10x better in their category on a standalone basis, and we will never take our ability to cross-sell for granted.

Source: Robinhood S-1

There are signs of early scale in action, with Robinhood decreasing margin interest rates, effectively passing scale efficiency savings onto the customer as unit economics evolve.

Conversely, there are multiple examples of scale hurting Robinhood’s business. Several times over the past few years (the March 2020 Outages, the April-May 2021 Outages, the Early 2021 Trading Restrictions) Robinhood has experienced platform shutdowns due to surplus usage, signifying scale may be happening, but not efficiently. Part of this can be attributed to absurd growth, part due to poor preparation, but either way, the spotty scale execution does not merit a moat rating.

Robinhood’s Network Effects

The product becomes more valuable as more customers use the product

My favorite examples of the Network Effects moat are social media, or peer-to-peer transaction companies like Square (SQ) or PayPal (PYPL). While Robinhood may not benefit from Network Effects today, I believe Robinhood is excavating the foundation for this moat. There are multiple references in the S-1 towards building out a peer-to-peer transaction network within Robinhood, which would be a powerful, dark-horse entry into the cutthroat space of digital banking (more on this later).

Education similarly is a crucial Network Effects vertical for Robinhood to take advantage of. Robinhood’s widely used resources Robinhood Snacks (32 million subs) and Robinhood Learn (7 million page views) are building financial literacy, yes, but more importantly, are building a community.

Community is the oxygen-delivering circulatory system of Network Effects. Instagram is cool because all your friends are on it. Venmo is popular because each of your friends use it. Unfortunately for Robinhood, their current community is one-sided. Users can listen to the Robinhood Snacks podcast, but cannot interact, submit investment ideas or challenge other users. An acquisition of a financial social media platform such as Discord (probably too expensive, and might have to leapfrog Microsoft) or Seeking Alpha would add needed depth to this budding moat. If I were Tenev, I wouldn’t stop there. Further investment could be used to acquire financial podcasters or even Substack writers to prepare content only accessible to Robinhood users (I think with this post I am writing myself out of contention 😅). Hoarding content available only to MAU’s is an eight-lane highway to Network Effects realized.

Robinhood’s Switching Costs

Customers would incur value loss if they switched to a different product supplier

This is another moat Robinhood cannot claim. Perhaps when Robinhood first announced commission-free trades this could be considered the beginnings of a moat, but clearly not defensible as traditional brokerages uniformly adopted commission-free trades in 2019 (although it cost them roughly $1.6 Billion annually to do so). Furthermore, as outlined above, Robinhood has a checkered history at best with ‘price improvement;’ customers might actually save money by switching to another brokerage.

Opportunities here are myriad, but the most intriguing options are likely in cryptocurrency and decentralized finance (DeFi). Look no further than ‘staking’ cryptocurrencies, popularized by BlockFi and most recently, Coinbase (COIN). This is the process of ‘loaning’ the crypto you own back to the platform you hold it on. In return, the platform arbitrages market inefficiencies to deliver astronomical interest rates (4 – 8.6%) back to the user in the form of dividends (often monthly or weekly). If Robinhood allowed users to stake their crypto on the app and was able to deliver higher interest rates than competitors, this could get interesting. It would be a broadside salvo at new crypto entrants, obviating many. While titillating to contemplate, I see no evidence for Robinhood’s involvement here as of yet. In the meantime, I expect Robinhood to continue offering new alt-coins, as well as the functionality to withdraw and deposit crypto to/from Robinhood.

Robinhood’s Process Power

Embedded company organization and activity sets enabling lower costs and/or superior product, and which can be matched only by an extended commitment

Robinhood’s S-1 is brimming with sesquipedalian terminology sensationalizing completion of their own, proprietary clearing house. This reads a lot like process power:

With a focused team and appropriate regulatory approvals, we created our own clearing platform. Our platform is entirely cloud-based and built on proprietary, API-driven services to meet the needs of a fast-growing, mobile-first, modern financial institution. Our platform also enables a vertically integrated, end-to-end approach to product development, which helps us move faster from idea to creation, empowers us to better scale with the growth of our business and affords us better unit economics that we can share with our customers.

Source: Robinhood S-1

Sounds awesome. But it turns out this is not so proprietary – all the major brokerages are self-clearing, so this was actually a relative deficiency in Robinhood’s stack prior to development. This is not a moat.

Of the first four moats we have outlined, process power is Robinhood’s least developed moat, and I see no evidence of future differentiation here from my research.

Robinhood’s Counter-Positioning

A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model, which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business

For as weak as Robinhood is on the first four moats we’ve discussed, Robinhood is perhaps the poster child of the counter-positioning moat; the quintessential newcomer exercising superior strategy incumbents cannot implement without cannibalizing revenues. Businesses that execute counter-positioning to the highest degree end up either bankrupting the incumbent or imposing evolution to the new business model. Robinhood has achieved the latter, devastating traditional brokerages’ commission revenues and forcing consolidation (Schwab and TD Ameritrade).

Traditional brokerages remained frozen in indolence for the first few years after Robinhood’s launch, silently monitoring the meteoric rise of the retail investor, gargantuan mouths increasingly agape.

Take a moment to wonder with me how different Robinhood’s user acquisition slope would look had Schwab offered commission-free trades in 2016…

Underestimation of Robinhood’s value proposition and the importance of the underserved retail investor has made traditional brokerages look less like Blue-Chip and more like Blockbuster Video. This is a moat, even and especially now as Robinhood aims to take new business verticals from incumbent banks and fintech platforms alike.

Robinhood’s Cornered Resources

Preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value

This may be controversial, but I believe Robinhood can claim this moat as well. No, I am not referencing the addictive nature of their offerings. Much like gambling, cigarettes or social media, Robinhood’s product fuels a dopa-driven reward cycle that is tough to quit, and therefore the business is resilient. But Robinhood is not the only trading company with these features.

Nor do I think Robinhood has differentiated technology than competitors despite what the founders have said in interviews. Bhatt has made the claim Robinhood’s products are 10x better multiple times, referencing Peter Thiel’s famous quote on the topic. I see no proof of this – Robinhood offers financial trading on a technology stack virtually indistinguishable from incumbents. It’s a prettier interface, yes, and perhaps more intuitive UX, but not 10x more so. Lastly, I do not believe Robinhood’s leadership or engineering talent constitutes a brain trust the way it might in a Stripe or a Palantir.

Actually, I believe I am Robinhood’s cornered resource. Me.

Well, me and 17.99 million others who use Robinhood’s products. Hear me out. There is a well-used adage in the technology space that aptly captures this sentiment:

“If you’re not paying for it, you’re the product.”

Given the vast majority of Robinhood’s revenue comes from selling retail investor data, users are the product. This is a not-too-dissimilar business model from Facebook. But unlike Facebook or Instagram, which are platforms for everyone, Robinhood is a platform for a very specific demographic: the underserved retail investor.

Whether or not you are bullish on Robinhood, it’s tough to argue the company has not enabled the retail investor. In the case of many users, Robinhood has dramatically foreshortened the closeness of financial independence. Indeed, Robinhood cites a $25 Billion increase in the net asset value of its users – gains realized on the Robinhood platform. And this community of retail investors is dynamic. They collaborate on platforms like Discord, Seeking Alpha and Reddit, they scheme and coordinate buy times, they argue and refine their investment theses, and have caused hedge fund colossi to lose billions. This is a powerful cohort of users.

And when you look even closer, the empowerment of this group is more evident.

Three years ago I convinced my mother to open a Robinhood account. By way of background, if I were to author my mother’s biography, the word ‘frugality’ would appear more often than the word ‘lawsuit’ appears in the Robinhood S-1 (37). Despite her prudent nature, she never felt included in The Great Investment Game – she never felt there was an avenue to grow wealth outside of a savings account. And so she didn’t.

Once she opened a Robinhood account, she began saving small but consistent amounts every few weeks, purchasing stocks I pitched to her. As time passed she began following updates on her holdings, watching Mad Money and listening to finance podcasts, and seemed to genuinely enjoy engaging me on business news. She has even begun shrewdly calling her own shots (recently almost tripled her Moderna position in a few months). She has never made a crypto or options trade, and borrows no margin.

Over the past three years her portfolio has enjoyed an almost vertical slope of price appreciation (see below), resulting in a six-digit windfall. She is considering liquidating her Robinhood holdings to move from a rental property to owning a home.

Source: Screenshot from my momma Okland’s phone

This seems like magic to me. Seeing my parents enjoy the fruits of disciplined investing on the Robinhood platform is one of reasons I am most conflicted about writing a negative stance on the company.

There is something so inevitably hard about saving, that when financial independence is brought nearer, even marginally so, beautiful things can happen. Passions can be explored and realized, communities built and opportunities claimed.

Myself, I was a Robinhood investor who read so much financial analysis I decided to do it myself. My experiences with Robinhood motivated me to investigate the business world comprehensively, and I consume vast amounts of financial news on a daily basis. And it’s not like I don’t have a full time job (or two). I have enjoyed writing financial articles so much I wake up at 3 am to get in a few hours of research or writing before rounds or before my fiancé wakes up, listen to CEO interviews while I exercise, and my version of ‘social media’ is not TikTok, but Seeking Alpha. Robinhood was the launching pad for this passion to take flight.

Robinhood’s users as a moat is borne out in the numbers. 80% of new funded accounts in the three months ended March 31, 2021 joined organically or through the referral program. Users check the app more than double (and oftentimes higher) competitors, and the Robinhood community foments FOMO on a seemingly daily basis, resulting in higher-frequency trading. And because Robinhood is at its core a transaction company, FOMO is a revenue multiplier for Robinhood.

Robinhood’s users, if they can protect and cultivate them, are a cornered resource. This is a moat. Users can perpetuate TAM expansion on an individual or cohort basis, develop platforms of their own, and shepard new investors to the fold.

This is not to say every Robinhood user has experienced net asset appreciation. Far from it. In many cases individuals have lost most if not all of their investments. While I don’t have access to the data, I imagine the worst examples of this are due to margin or options trading, which is a failure shared between Robinhood and the user.

Users must be educated adequately about the relative risks of trading, but also must take the time to educate themselves prior to executing trades. With the infinite educational resources of the internet today, it’s hard for me to be completely sympathetic to an individual who lost $1k on an options trade and then blames Robinhood for inadequate education. That’s not investing. Would you feel equally bad if the individual lost that amount on a UFC bet? I’d wager not. Regardless, Robinhood can and must do a better job highlighting risks and providing educational content to introduce speed bumps into riskier investments.

Because Robinhood has so few moats, and because its Cornered Resources moat is so vital, I will be carefully following Robinhood’s commitment to its users. Users, more than Dogecoin, more than options spreads, above all else, are the most important characteristic of Robinhood’s business.

Robinhood’s Branding

The durable attribution of higher value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historical information about the seller

It’s hard for me to remember a shinier penny than Robinhood was in 2019. It was an absolutely treasured fintech darling. Users raved about Robinhood and incumbents feared its growing power. The elegant design that allowed Robinhood to be the first FinTech company to win an Apple Design award was just plain cool; all clean lines and neon lime lightning bolts. Had I written this article in early 2019, I might have featured Robinhood’s Branding as a moat, with commission-free trading, faster and easier trade execution, and an unconscious perception that Robinhood was just better than traditional brokerages.

Source: My Two Cents: A Robinhood Growth Analysis

Look at the difference here. For an amateur investor, which app appears more accessible, and clean?

As I prepare this article, covering Robinhood has caused me to question Helmer, and whether branding truly constitutes a moat. In its ideal form, a moat confers enduring value; it allows a competitive advantage defensible for a decade or more. But over the past two years Robinhood’s slick chrome brand has cracked, like a cheap veneer. This suggests what many might intuit, that there is something inherently fragile about a company’s brand. If scale economies and network effects are the iron bellows of a business, the brand might be something elegant and transparent, like glass, and similarly brittle.

My conclusions are twofold:

1.) Robinhood once enjoyed the Branding moat, but no longer does.

2.) Branding is perhaps the weakest of the seven powers, and may not constitute a moat at all.

Losing this moat does not appear to have deterred user growth, and Robinhood boasts the highest revenue growth rates of any publicly traded company I cover (besides one I mention later). That said, Robinhood appears to recognize they have lost this public perception, and are doubling down on rebuilding it.

Our brand has faced challenges in recent years…We take these concerns seriously and have prioritized developing responsive solutions…We are determined to continually evolve to better serve our expanding customer base.

Source: Robinhood S-1

In the meantime, cast ‘Branding’ in the ‘Moats Lost’ category.

The Hallowed Robinhood S-1

Many excellent writers have taken the opportunity to highlight the recently released Robinhood S-1. However, I wish to emphasize three key takeaways that are both 1.) under-discussed in the financial literature and 2.) crucial to understand the business and coming IPO.

S-1 Mentions:

Tenev 102

Bhatt 91

PFOF 65

Lawsuits 37

Bitcoin 20

Dogecoin 10

International expansion 7

Single money app 5

Insight No. 1: Robinhood is posting industry-leading growth rates

In an industry where growth is ubiquitous and expectedly vertical, Robinhood is the belle of the ball. For Q1 2021, Robinhood posted breathtaking acceleration in growth, well-exceeding the definition of a ‘growth story.’

Source: Robinhood S-1

Quarter over quarter, Robinhood grew funded accounts by 5.5 million, or 44%. To put this in context, on January 1, 2020, Robinhood had 5.1 million users. Robinhood gained more than that in the most recent quarter. Absurdity.

Revenue grew 309% year over year to $522 million, with transaction revenues (PFOF), net interest revenues, and other revenues constituting $420.4 million, $62.5 million and $39.2 million, respectively. Whereas transaction revenue was 62% of 2019 revenues, this has steadily climbed to 75% in 2020 and now 81% in Q1, 2021. Within this segment, equity revenue grew 322%, options revenue grew 231%, and cryptocurrency revenue grew 1,967%.

Most intriguingly, Dogecoin, mantle of the Shiba Inu meme, and motif of splashy moon-related Musk musings, comprised a full 34% of cryptocurrency revenue. Said much more plainly, revenue from Dogecoin trading accounted for nearly 6% of Robinhood’s entire Q1 2021 revenue.

While I never like to see revenue concentration, it bears mentioning Dogecoin rounded out the month of March with a value near $0.05/coin. Over the past three months the meme coin has flirted briefly above $0.70 before settling out around $0.20 today. This volatility (roughly 88x increase in $DOGE trading volume at its peak in April compared to March 31, according to CoinMarketCap), combined with the 4x increase in coin value should confer meaningful upside to Robinhood’s Q2 2021 numbers.

Ironically, this will probably prompt analysts to worry more dourly, as the relative contribution from $DOGE will be even higher. They did this with Etsy’s (ETSY) mask sales too, to their detriment. Money is money, and crypto is headed higher.

Subscription rates have far exceeded growth expectations as well. Robinhood Gold users leapt from 0.3 million to 1.4 million year over year, and 0.5 million are currently using Robinhood’s margin lending product. A full 40% of these customers were acquired in the first three months of 2021, growth of 66% quarter over quarter. In Q1 2021 total margin lent by Robinhood pulled an Aunt Marge, ballooning to $5.4 Billion from an already weighty $661 million. This results in $245 in revenue per margin customer, or $122.5 million in annual recurring revenue.

And Robinhood is improving profitability. Although operating expenses increased 158% year over year, as a percentage of net revenues expenses dropped from 141% in 2020 to 89% in the most recent quarter. Barring the previously mentioned convertible notes and warrant liability charge of $1.5 Billion, Robinhood posted adjusted EBITDA of $114.8 million for Q1, well on track for another profitable quarter.

There is much to digest in the numbers alone, and frankly, the quarter over quarter numbers would be excellent results for most companies over a three year period. Bottom line – outside of pure-play crypto firm Coinbase, I have never followed nor heard of a company this size growing this fast. Coinbase (COIN), which I own, posted higher revenues and profitability in Q1, but they are strictly a cryptocurrency business. Comparing crypto segments, even Coinbase isn’t growing crypto revenues 2,000%.

Insight No. 2: Robinhood Has SoFi, Square & PayPal In Its Crosshairs

It seems like the Fintech Kings are sharing notes on strategy. While I have written extensively about SoFi and Square’s aggressive pursuit of the ‘single money app’ holy grail, I was curiously unaware of Robinhood’s frank aspirations to lead this charge.

Five times throughout the S-1 Robinhood hammered home the importance of building the ‘single money app.’

As we look to the future, we want to help Robinhood customers manage all aspects of their financial lives in one place. We envision them moving seamlessly between investing, saving and spending all on the Robinhood platform. When we check our email, there is a go-to app. When we need a map, there is a go-to app. We envision a world in which Robinhood is that go-to app for money. We believe people want to build financial independence and have the tools and ability to own their financial well-being. We look forward to being our customers' single money app that enables them to achieve those goals.

Source: Robinhood S-1, emphasis mine

This is a direct broadside at SoFi’s business model, and to a lesser extent, Square. But Robinhood doesn’t stop there – it follows up with a declaration of war on both Square and PayPal.

We see a significant opportunity to introduce innovative products to address our customers’ future needs—including investing, saving, spending and borrowing—allowing us to grow with new and existing customers from our single money app. additional opportunities are significant—for example, U.S. credit card purchase volume was approximately $3.6 trillion in 2020 (according to Nilson Report), and there is an approximately $4 trillion volume opportunity in peer-to-peer and micro-merchant payments (according to Square, Inc.).

Source: Robinhood S-1, emphasis mine

The boldness of these claims cannot be overstated. To take on SoFi is one thing; SoFi has less than an eighth of Robinhood’s users and has a long way to go towards offering a similarly competitive trading product. But Square’s CashApp and PayPal’s Venmo? Beware Vlad, here be monsters. These peer-to-peer (P2P) payments platforms boast nearly 100 million users between them, hundreds of billions in market cap and an outstanding head start.

While I see PayPal more as a mature business at this point and less agile (recent increase in transaction prices to $3.49% + $0.49 per transaction makes a good case PayPal is sacrificing growth for profitability), Square in particular will be a tough opponent to tangle with. Jack Dorsey is a generational marketing wizard responsible for the lowest CAC’s in fintech.

That said, Robinhood undeniably has a superior trading platform with more functionality than either of the incumbents (feels weird calling Square an incumbent), which I believe is potentially stickier than P2P transactions. P2P transactions depend primarily on family and friends also using the platform (Network Effects). But, if 100 people in a community are each using P2P on Venmo, CashApp, and Robinhood, the technology becomes commodity, and the platform with the greatest functionality (ie, the single money app) wins. While I do not believe only one player will win in this space, I do see a scenario where Robinhood takes a large, if not top-two share.

In regards to future innovation, and based on a close reading of the S-1, I see Robinhood implementing the following three strategies over the next year.

1. Launching a peer-to-peer product

2. Expansion of offerings internationally, starting with the U.K.

3. Banking charter application submission

If I were Tenev, calling an all-hands on the long-term vision of newly public Robinhood, these are the goals I would lay out. They are massive, risky, and target trillion dollar categories head on. I love big bets and moonshots, and these are worthy of the ‘Category-Defining’ brand Robinhood believes it is.

Insight No: 3: Robinhood’s Business Does Not Always Align with Customers

Whether you realize this implicitly or have derived it yourself, Robinhood’s business is not driven by empowering ‘buy and hold’ investors as is claimed. Even a wayward glance at Robinhood’s Q1 2021 numbers reveals Robinhood is, for all economic intents and purposes, an options brokerage.

In Q1, 2021 Robinhood pocketed 0.2%, 1.2% and 9.5% of customer’s quarter end equity trading volume, cryptocurrency trading volume, and options trading volume, respectively. These results are in one quarter alone.

If you were a business, which of the three would you most want your customers to engage with?

Take a hypothetical customer, Saul. Saul has $10k in his Robinhood account. If Saul trades roughly $10k worth of equities in a given year, Robinhood will be able to extract 0.8%, or $8 dollars of annual revenue. On the other hand, if Saul trades $10k in crypto, Robinhood will pocket 4.8%, or $48 dollars. But the real cheddar is in options trades. And if Saul is a YOLO’ing low-slung options trader compelled by his diamond-handed friend of an acquaintance to BTFD on fat GameStop calls, Robinhood could claim 38%, or $3,800. 🚀🚀🚀

To the moon, indeed.

There’s something about financial news I appreciate more than all other medias – it’s just numbers. And when it comes to the Robinhood S-1, the numbers speak plainly. Sure most Robinhood customers may be buy and hold investors, but that’s not where Robinhood enjoys its meals.

Robinhood collects its fattest profits from the riskiest trading behavior.

My chief, and almost instinctual concern regarding this business model is that it does not align with its customers’ financial interests. To say retail investors engaging in voluminous equity/options/dogecoin trading may not be the best investment strategy seems like lazy sophism. Price elasticity (the bespectacled cousin of supply and demand) is a fundamental tenet of investing – the more expensive an asset is priced the less people want to purchase. But similarly, a fundamental tenet of FOMO is that if your friends made money on GME flying from $100 to $300/share, you need to buy at $300 to repay the debit on missing out. This flies in the face of common sense, financial literature, much less capital gains tax.

I can recount numerous times in February scrubbing into cases with circulating nurses or anesthesiologists asking me how much GameStop or AMC stock I owned. My reply?

“I am an investor, not a gambler.”

Although this admittedly reads as snooty, it isn’t intended to be. Meme assets are divorced from fundamentals – the most voluminously traded assets in Q1 2021 were broken businesses. My primary goal as an investor is to identify superlative businesses that are under-recognized or undervalued. Can you see how this philosophy is in diametric opposition to the meme stonk movement?

Robinhood is financially incentivized to encourage riskier and more frequent investing. Their product is addictive, used by customers who are primarily amateurs, and the harms of financial insolvency are not intangible. As a potential HOOD investor, I find this troubling, as one might find investing in JUUL, troubling.

The Coming $HOOD IPO

After years of “will they, won’t they” rumors, the day after FINRA imposed their $70 million fine, the S-1 dropped. Robinhood set the table for an IPO.

(While you can make your own assessment re Robinhood celebrating its future IPO within 24 hours of receiving the largest such fine in history) I was encouraged to see Tenev making good on his promise to earmark shares to Robinhood users at the IPO price (20-35% of shares will be available to Robinhood users), and believe this is a cathartic conclusion to one of the most controversial histories I have heard of, much less chronicled. I was less encouraged to hear Robinhood has been valued upwards of $55 Billion in the secondary markets, and it got me thinking about the price I would be willing to become a Robinhood investor at.

If you cannot tell from my writing, I am conflicted about this company. I see, and relate to both camps. But, as I am a Robinhood user and intend to remain one (until/if SoFi or Square improve their offerings), I am not sure I can maintain any moral high ground by refusing to invest in the company. That said, I can discount its intrinsic value due to well-founded concerns regarding its business model, values, and propensity to fuck up.

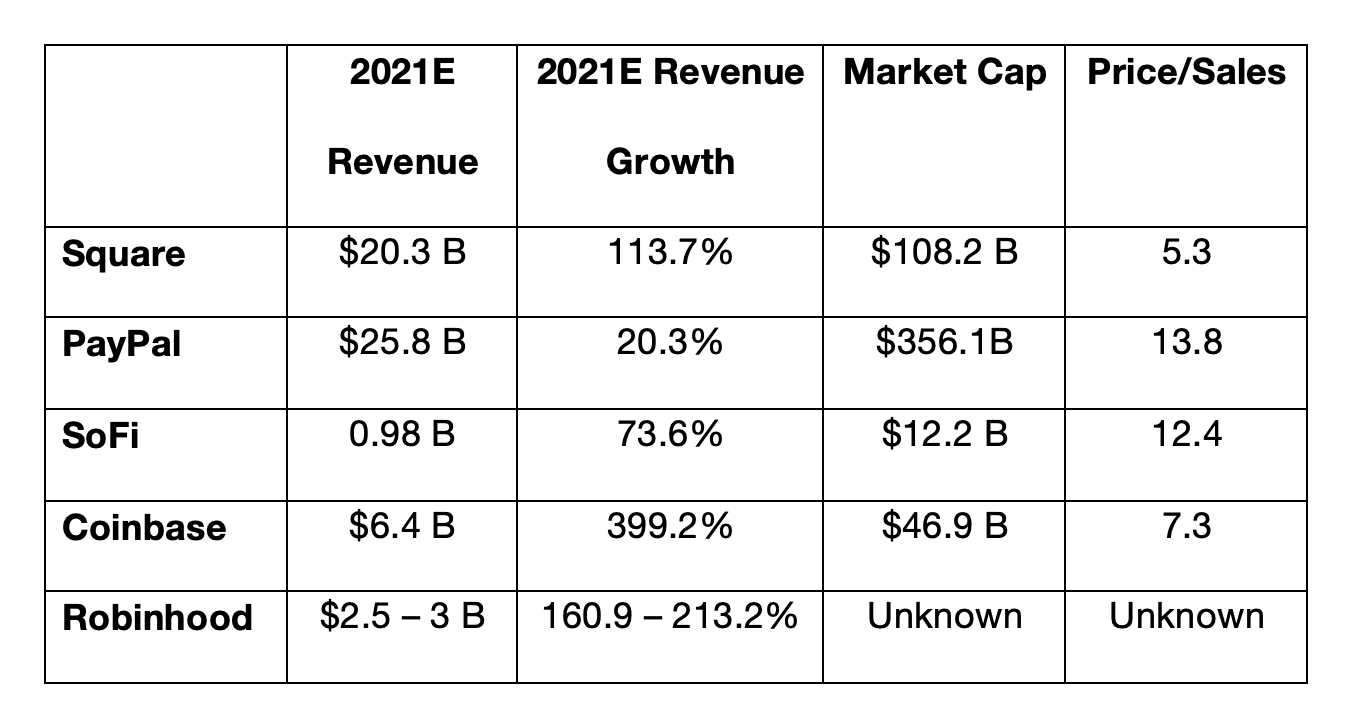

Below are my financial assumptions as well as my valuation model. I am using peers SoFi, Square, Coinbase and PayPal for comparison.

Assumptions:

o Robinhood posts $2.5 – 3 Billion in revenue in 2021, and $450 in adjusted EBITDA

o Robinhood launches no further equity raises in 2021 (emphasized in the S-1)

Robinhood and its Peers

Source: Data obtained from Seeking Alpha

The median price to sales (P/S) here is roughly 10, although Robinhood’s growth is multiples higher than some of its peers. In addition, there has been a multiple compression in high growth fintech names recently – at one point the P/S multiples were almost a full double for each of these stocks. Consequently, I may be underestimating Robinhood’s value (which I am fine with).

I believe Robinhood warrants a (premium) P/S of 12 - 15, given its user growth, revenue velocity, and transparency regarding future growth endeavors. However, given my outlined concerns regarding Robinhood’s business, I discount 20% of that value to arrive at what I would consider an investible entry.

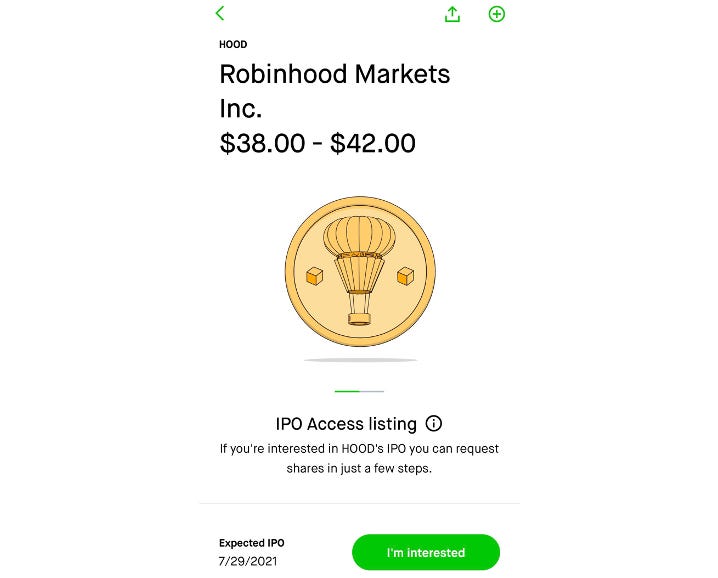

We are introducing a few variables here, but overall that results in a range of values of $24 to $36 Billion, or an average of $30 Billion. At a share price corresponding to this market cap, yes, I would entertain a position.

Just before publishing this article, I recieved a notification from Robinhood that Robinhood Markets Inc, ticker $HOOD, is now available on Robinhood, at a price of $38 - 42/share. At the high end of this range, Robinhood would be valued at $35.3 Billion, at the low end it would be valued at $31.7 Billion. As outlined above, this is right within what I consider fair value.

However, I expect the IPO price to rise outside this window — retail investors might have qualms about buying $HOOD, but Robinhood is a fintech colossus growing faster than just about anyone. Accordingly, I anticipate institutional demand for $HOOD to border on frenzied. To be clear, I expect a pop higher, but my firm price is as above.

Wrapping It All Up

Betrayal is an interesting thing. You cannot be betrayed by your enemies or even vague acquaintances, only those you’ve placed your trust in. Perhaps this is why the Robinhood topic is so polarizing. People really care.

My feelings about Robinhood are clearly complicated. Like all messy stories, I’ve likely written too much, and inevitably left much unsaid. But I hope I was able to deliver to you both sides of the story.

Understanding the Robinhood narrative, the tension between good and evil, is critical to form an educated position on its offerings. And that’s my primary goal as a writer – to deliver misunderstood investment ideas and opportunities. To clarify the obscure, and unify the frayed tangles of a story in all its kaleidoscopic colors.

I don’t believe Robinhood is evil. Nor do I think it and its founders are intrinsically good. Robinhood is a business, and a for-profit one. That said, in many ways Robinhood’s business is aligned against the investors it promises to empower, which I find problematic. In my ideal investment, a business gains strength when the customer wins, and loses when the customer loses.

That’s not Robinhood.

Thank you for reading this, my first Substack post. I’d love to hear your comments, concerns, and ideas below. If you enjoyed this, please share widely with your friends, family, and investing community.